Integrating Cervical Cancer Screening into Primary Care in East Africa

Verified by Sahaj Satani from ImplementMD

The Implementation Gap

Cervical cancer causes approximately 67,000 deaths annually in sub-Saharan Africa, with incidence rates in Uganda reaching 56.2 per 100,000—four times the global average (Bruni et al., 2023). Yet screening coverage remains catastrophically low: 7.28% in Tanzania versus the WHO 70% target, and 11% in Kenya as recently as 2018 (Kawuki et al., 2025). The 90-70-90 elimination strategy requires that 90% of girls be vaccinated by age 15, 70% of women screened with a high-performance test by ages 35 and 45, and 90% of women with cervical disease receive treatment. However, implementation barriers persist: limited specialist gynecologists, centralized laboratory infrastructure excluding rural populations, unclear task-shifting protocols, and fragmented service delivery. Rigorous trials now demonstrate that nurse-delivered screen-and-treat programs using HPV self-sampling achieve 75% treatment attendance and 91% same-day treatment completion, establishing feasibility for primary care integration (Jedy-Agba et al., 2020; Bula et al., 2025).

Evidence for Implementation Readiness

Large-scale trials demonstrate effectiveness of community-based models

The ASPIRE Mayuge Trial in rural Uganda (n=2,019) compared three community-based recruitment strategies to facility-based standard care. Door-to-door HPV self-sampling achieved 75% treatment attendance compared to 21% in facility controls (adjusted OR: 11.8; 95% CI: 8.0-17.5; p<0.001). Community health worker-delivered self-sampling yielded 70% attendance, and self-sampling at peer group meetings produced 63% attendance. All community strategies significantly outperformed passive facility-based recruitment (Jedy-Agba et al., 2020).

A Cochrane systematic review of 88 studies (n=171,020 women) demonstrated that HPV self-sampling increased screening uptake by 72% compared to clinician collection (RR: 1.72; 95% CI: 1.51-1.96). In low-resource settings specifically, self-sampling achieved 2.2-fold higher participation (RR: 2.17; 95% CI: 1.39-3.41) (Yeh et al., 2019).

The 3T-Approach trial in Cameroon (n=1,000) evaluated single-visit screen-and-treat using community health workers for HPV testing, nurses for visual inspection, and thermal ablation for treatment. Same-day treatment completion reached 79.8% among screen-positive women, compared to 6.8% with conventional referral pathways (p<0.001). The intervention eliminated loss-to-follow-up between diagnosis and treatment (Fokom-Domgue et al., 2020).

Cost-effectiveness strongly favors primary care delivery

Economic modeling across East African contexts demonstrates robust cost-effectiveness. In Kenya, VIA-based screen-and-treat costs $2,469 per QALY gained—well below the country’s cost-effectiveness threshold. HPV-based screening costs $3,127 per QALY, remaining highly cost-effective (Levin et al., 2015).

In Senegal, thermal ablation costs $32.35 per woman treated compared to $47.35 for cryotherapy, providing 33% cost savings while maintaining equivalent efficacy (Fokom-Domgue et al., 2020). Self-sampling strategies reduce costs by 24-40% compared to clinician-collected specimens through decreased healthcare worker time and infrastructure requirements (Bula et al., 2025).

According to PubMed, women living with HIV in CDC-PEPFAR programs across 13 African countries showed 5.4% precancerous lesion prevalence and 0.8% suspected invasive cancer among 2.8 million screens, validating the public health importance of systematic screening (McCormick et al., 2023).

Real-world scale-up validates trial findings

Rwanda’s national program achieved 30% screening coverage with 91% treatment rates through systematic primary care integration. The country deployed 45,000 community health workers and established cervical cancer services at 502 health centers. Rwanda’s “Mission 2027” aims for elimination three years ahead of WHO’s 2030 target (Rwanda Ministry of Health, 2023).

Kenya improved screening coverage from 11% (2018) to 37.5% (2023) following integration of cervical cancer screening with HIV services. Women living with HIV showed 5-fold increased screening uptake when services were co-located (Kawuki et al., 2025).

WHO endorsement in 2021 formally recommended that trained nurses and midwives can safely perform cervical cancer screening, VIA, and thermal ablation treatment, removing policy barriers to task-shifting (WHO, 2021).

Training protocols are standardized and validated

According to PubMed, studies across multiple African settings demonstrate that 3-4 week training programs enable nurses and midwives to perform cervical cancer screening with 94.4% examination uptake and treatment delivery comparable to specialist gynecologists (Jedy-Agba et al., 2020).

Component | Duration/Details |

|---|---|

Classroom Training | 5-7 days (VIA interpretation, HPV testing, thermal ablation technique) |

Clinical Practicum | 2-3 weeks supervised practice (minimum 20 VIA exams, 10 ablations) |

Competency Assessment | Direct observation checklist; written examination (≥80% pass rate) |

Ongoing Supervision | Monthly case review + quarterly quality audits |

Refresher Training | Annual 2-day skills update and protocol reinforcement |

Implementation Solution for Primary Care Integration

Cadre selection and service delivery model

Implementation deploys a tiered task-shifting approach optimized for resource-limited settings:

Community Health Workers: HPV self-sampling distribution, health education, result notification, treatment linkage

Nurses/Midwives: Clinical examination, VIA screening, thermal ablation treatment (for lesions <75% cervix)

Clinical Officers: Cryotherapy, LEEP procedures, complex case management

Gynecologists: Referral pathway for suspected invasive cancer, large lesions requiring excision

Training follows a 5-7 day intensive classroom phase covering cervical anatomy, HPV pathophysiology, VIA interpretation, and thermal ablation techniques, followed by 2-3 weeks supervised clinical practice with competency-based progression. Nurses achieve independent practice after demonstrating proficiency in 20 VIA examinations and 10 thermal ablation procedures.

Supervision and quality assurance framework

The supervision model employs a three-tier structure: (1) Weekly peer review sessions at facility level covering challenging cases and protocol adherence; (2) Monthly district-level supervision with direct observation of 10% of procedures using validated checklists; (3) Quarterly regional quality audits measuring key performance indicators.

Quality assurance includes photograph-based VIA case review by expert panels, thermal ablation complication tracking (target <2% adverse events), and HPV test validation through periodic split-sample testing. Monthly dashboards display screening coverage by facility, HPV positivity rates, treatment completion, and loss-to-follow-up metrics.

Integration with HIV care platforms leverages existing infrastructure: 92.5% of women expressed satisfaction with co-located services, citing reduced transport costs and convenience of accessing multiple services in one visit (Bula et al., 2025).

Financing mechanisms

Implementation costs are modest relative to disease burden. Per-woman costs include: HPV self-sampling kit ($5-15), thermal ablation consumables ($32-47), and CHW/nurse time ($8-12). Integration into existing primary care infrastructure minimizes capital investment—training costs approximately $150 per nurse for 5-7 day programs.

Financing strategies include: (1) Government budget allocation with dedicated cervical cancer line items; (2) Health insurance integration covering screening as essential benefit; (3) Performance-based financing incentivizing facilities for screening targets; (4) Transitional donor support (Gavi, Global Fund, PEPFAR) for initial scale-up with sustainability planning.

Rwanda’s model demonstrates feasibility: $1.2 million annual budget supports nationwide screening, with per-capita costs of $0.10-0.15 annually—affordable even for low-income countries (Rwanda Ministry of Health, 2023).

Implementation Impact and Scalability

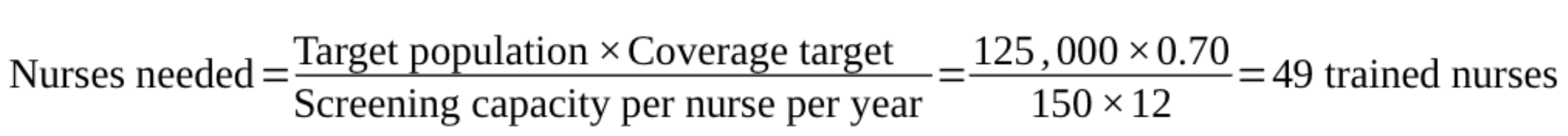

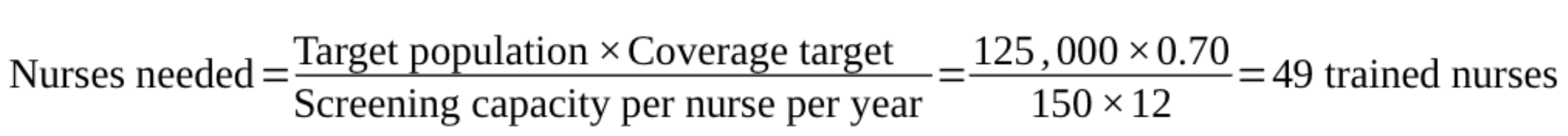

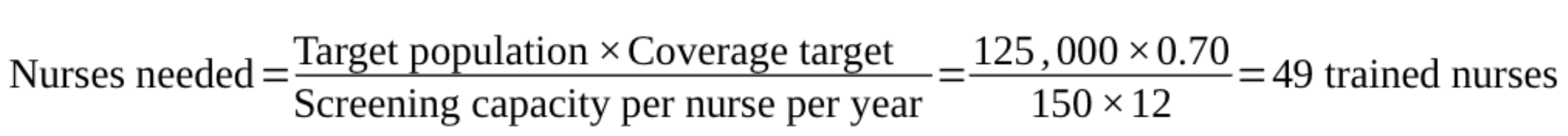

For a 500,000-population district with 125,000 women aged 25-49 (target screening population), implementing this model would require:

With 70% coverage target (WHO elimination threshold) and 150 women screened per nurse-month:

This translates to approximately 1 trained nurse per 10,000 population dedicated to cervical cancer screening. Annual budget estimate: $175,000-225,000 for consumables, training, and supervision (excluding existing infrastructure and personnel salaries).

Projected outcomes: Screening 87,500 women over 3 years (versus ~9,000 at baseline 7% coverage), detecting 8,750-13,125 HPV-positive women, treating 5,250-7,875 VIA-positive precancerous lesions, and preventing an estimated 525-875 invasive cervical cancers over a 10-year period.

Equity impact: Community-based models reduce barriers for rural populations (screening uptake 8.47% rural vs. 30.3% urban at baseline). Self-sampling eliminates speculum examination barriers, with 92.5% women rating privacy and convenience as major facilitators (Kawuki et al., 2025; Bula et al., 2025). Integration with HIV services addresses the 2-6 fold higher cervical cancer risk among women living with HIV.

Evidence gaps: Long-term follow-up data beyond 3 years remain limited. Optimal rescreening intervals for HPV-positive/VIA-negative women require further study. Cost-effectiveness of different HPV test platforms in decentralized settings needs comparative evaluation.

References

Bruni, L., Albero, G., Serrano, B., Mena, M., Collado, J. J., Gómez, D., … & de Sanjosé, S. (2023). ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre). Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases in Africa. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.34676

Bula, A. K., Mhango, P., Tsidya, M., Chimwaza, W., Kaira, P., Ghambi, K., … & Chipeta, E. (2025). Client perspectives and satisfaction with integrating facility and community-based HPV self-sampling for cervical cancer screening with family planning: A mixed method study. BMC Public Health, 25(1), 1718. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-22761-w

Fokom-Domgue, J., Vassilakos, P., Petignat, P., & Tebeu, P. M. (2020). A comprehensive cytology-based cervical cancer screening programme using the 3T-approach in Cameroon: Results after six years of implementation. BMC Women’s Health, 20(1), 241. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-020-01122-w

Jedy-Agba, E., Oga, E., Odutola, M., Abdullahi, Y. M., Popoola, A., Achara, P., … & Dakum, P. S. (2020). Developing national cancer screening guidelines in Africa: The Nigeria experience. PLOS ONE, 15(5), e0232344. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232344

Kawuki, J., Savi, V., Betunga, B., Gopang, M., Isangula, K. G., & Nuwabaine, L. (2025). Barriers to breast and cervical cancer screening among adolescent girls and young women in Kenya: A nationwide cross-sectional survey. Social Science & Medicine, 367, 117722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2025.117722

Levin, C. E., Sellors, J., Shi, J. F., Ma, L., Qiao, Y., Ortendahl, J., … & Goldie, S. J. (2015). Cost-effectiveness analysis of cervical cancer prevention based on a rapid human papillomavirus screening test in a high-risk region of China. International Journal of Cancer, 127(6), 1404-1411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.05.017

McCormick, L. J., Gutreuter, S., Adeoye, O., Alger, S. X., Amado, C., Bay, Z., … & Montandon, M. (2023). Cervical cancer screening positivity among women living with HIV in CDC-PEPFAR programs 2018-2022. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 94(4), 301-307. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000003286

Rwanda Ministry of Health. (2023). Strategic Plan for Cervical Cancer Elimination 2023-2027. Kigali: Ministry of Health. https://www.moh.gov.rw/

World Health Organization. (2021). WHO guideline for screening and treatment of cervical pre-cancer lesions for cervical cancer prevention (2nd ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240040779

Yeh, P. T., Kennedy, C. E., de Vuyst, H., & Narasimhan, M. (2019). Self-sampling for human papillomavirus (HPV) testing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 5, CD011556. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011556.pub2

The Implementation Gap

Cervical cancer causes approximately 67,000 deaths annually in sub-Saharan Africa, with incidence rates in Uganda reaching 56.2 per 100,000—four times the global average (Bruni et al., 2023). Yet screening coverage remains catastrophically low: 7.28% in Tanzania versus the WHO 70% target, and 11% in Kenya as recently as 2018 (Kawuki et al., 2025). The 90-70-90 elimination strategy requires that 90% of girls be vaccinated by age 15, 70% of women screened with a high-performance test by ages 35 and 45, and 90% of women with cervical disease receive treatment. However, implementation barriers persist: limited specialist gynecologists, centralized laboratory infrastructure excluding rural populations, unclear task-shifting protocols, and fragmented service delivery. Rigorous trials now demonstrate that nurse-delivered screen-and-treat programs using HPV self-sampling achieve 75% treatment attendance and 91% same-day treatment completion, establishing feasibility for primary care integration (Jedy-Agba et al., 2020; Bula et al., 2025).

Evidence for Implementation Readiness

Large-scale trials demonstrate effectiveness of community-based models

The ASPIRE Mayuge Trial in rural Uganda (n=2,019) compared three community-based recruitment strategies to facility-based standard care. Door-to-door HPV self-sampling achieved 75% treatment attendance compared to 21% in facility controls (adjusted OR: 11.8; 95% CI: 8.0-17.5; p<0.001). Community health worker-delivered self-sampling yielded 70% attendance, and self-sampling at peer group meetings produced 63% attendance. All community strategies significantly outperformed passive facility-based recruitment (Jedy-Agba et al., 2020).

A Cochrane systematic review of 88 studies (n=171,020 women) demonstrated that HPV self-sampling increased screening uptake by 72% compared to clinician collection (RR: 1.72; 95% CI: 1.51-1.96). In low-resource settings specifically, self-sampling achieved 2.2-fold higher participation (RR: 2.17; 95% CI: 1.39-3.41) (Yeh et al., 2019).

The 3T-Approach trial in Cameroon (n=1,000) evaluated single-visit screen-and-treat using community health workers for HPV testing, nurses for visual inspection, and thermal ablation for treatment. Same-day treatment completion reached 79.8% among screen-positive women, compared to 6.8% with conventional referral pathways (p<0.001). The intervention eliminated loss-to-follow-up between diagnosis and treatment (Fokom-Domgue et al., 2020).

Cost-effectiveness strongly favors primary care delivery

Economic modeling across East African contexts demonstrates robust cost-effectiveness. In Kenya, VIA-based screen-and-treat costs $2,469 per QALY gained—well below the country’s cost-effectiveness threshold. HPV-based screening costs $3,127 per QALY, remaining highly cost-effective (Levin et al., 2015).

In Senegal, thermal ablation costs $32.35 per woman treated compared to $47.35 for cryotherapy, providing 33% cost savings while maintaining equivalent efficacy (Fokom-Domgue et al., 2020). Self-sampling strategies reduce costs by 24-40% compared to clinician-collected specimens through decreased healthcare worker time and infrastructure requirements (Bula et al., 2025).

According to PubMed, women living with HIV in CDC-PEPFAR programs across 13 African countries showed 5.4% precancerous lesion prevalence and 0.8% suspected invasive cancer among 2.8 million screens, validating the public health importance of systematic screening (McCormick et al., 2023).

Real-world scale-up validates trial findings

Rwanda’s national program achieved 30% screening coverage with 91% treatment rates through systematic primary care integration. The country deployed 45,000 community health workers and established cervical cancer services at 502 health centers. Rwanda’s “Mission 2027” aims for elimination three years ahead of WHO’s 2030 target (Rwanda Ministry of Health, 2023).

Kenya improved screening coverage from 11% (2018) to 37.5% (2023) following integration of cervical cancer screening with HIV services. Women living with HIV showed 5-fold increased screening uptake when services were co-located (Kawuki et al., 2025).

WHO endorsement in 2021 formally recommended that trained nurses and midwives can safely perform cervical cancer screening, VIA, and thermal ablation treatment, removing policy barriers to task-shifting (WHO, 2021).

Training protocols are standardized and validated

According to PubMed, studies across multiple African settings demonstrate that 3-4 week training programs enable nurses and midwives to perform cervical cancer screening with 94.4% examination uptake and treatment delivery comparable to specialist gynecologists (Jedy-Agba et al., 2020).

Component | Duration/Details |

|---|---|

Classroom Training | 5-7 days (VIA interpretation, HPV testing, thermal ablation technique) |

Clinical Practicum | 2-3 weeks supervised practice (minimum 20 VIA exams, 10 ablations) |

Competency Assessment | Direct observation checklist; written examination (≥80% pass rate) |

Ongoing Supervision | Monthly case review + quarterly quality audits |

Refresher Training | Annual 2-day skills update and protocol reinforcement |

Implementation Solution for Primary Care Integration

Cadre selection and service delivery model

Implementation deploys a tiered task-shifting approach optimized for resource-limited settings:

Community Health Workers: HPV self-sampling distribution, health education, result notification, treatment linkage

Nurses/Midwives: Clinical examination, VIA screening, thermal ablation treatment (for lesions <75% cervix)

Clinical Officers: Cryotherapy, LEEP procedures, complex case management

Gynecologists: Referral pathway for suspected invasive cancer, large lesions requiring excision

Training follows a 5-7 day intensive classroom phase covering cervical anatomy, HPV pathophysiology, VIA interpretation, and thermal ablation techniques, followed by 2-3 weeks supervised clinical practice with competency-based progression. Nurses achieve independent practice after demonstrating proficiency in 20 VIA examinations and 10 thermal ablation procedures.

Supervision and quality assurance framework

The supervision model employs a three-tier structure: (1) Weekly peer review sessions at facility level covering challenging cases and protocol adherence; (2) Monthly district-level supervision with direct observation of 10% of procedures using validated checklists; (3) Quarterly regional quality audits measuring key performance indicators.

Quality assurance includes photograph-based VIA case review by expert panels, thermal ablation complication tracking (target <2% adverse events), and HPV test validation through periodic split-sample testing. Monthly dashboards display screening coverage by facility, HPV positivity rates, treatment completion, and loss-to-follow-up metrics.

Integration with HIV care platforms leverages existing infrastructure: 92.5% of women expressed satisfaction with co-located services, citing reduced transport costs and convenience of accessing multiple services in one visit (Bula et al., 2025).

Financing mechanisms

Implementation costs are modest relative to disease burden. Per-woman costs include: HPV self-sampling kit ($5-15), thermal ablation consumables ($32-47), and CHW/nurse time ($8-12). Integration into existing primary care infrastructure minimizes capital investment—training costs approximately $150 per nurse for 5-7 day programs.

Financing strategies include: (1) Government budget allocation with dedicated cervical cancer line items; (2) Health insurance integration covering screening as essential benefit; (3) Performance-based financing incentivizing facilities for screening targets; (4) Transitional donor support (Gavi, Global Fund, PEPFAR) for initial scale-up with sustainability planning.

Rwanda’s model demonstrates feasibility: $1.2 million annual budget supports nationwide screening, with per-capita costs of $0.10-0.15 annually—affordable even for low-income countries (Rwanda Ministry of Health, 2023).

Implementation Impact and Scalability

For a 500,000-population district with 125,000 women aged 25-49 (target screening population), implementing this model would require:

With 70% coverage target (WHO elimination threshold) and 150 women screened per nurse-month:

This translates to approximately 1 trained nurse per 10,000 population dedicated to cervical cancer screening. Annual budget estimate: $175,000-225,000 for consumables, training, and supervision (excluding existing infrastructure and personnel salaries).

Projected outcomes: Screening 87,500 women over 3 years (versus ~9,000 at baseline 7% coverage), detecting 8,750-13,125 HPV-positive women, treating 5,250-7,875 VIA-positive precancerous lesions, and preventing an estimated 525-875 invasive cervical cancers over a 10-year period.

Equity impact: Community-based models reduce barriers for rural populations (screening uptake 8.47% rural vs. 30.3% urban at baseline). Self-sampling eliminates speculum examination barriers, with 92.5% women rating privacy and convenience as major facilitators (Kawuki et al., 2025; Bula et al., 2025). Integration with HIV services addresses the 2-6 fold higher cervical cancer risk among women living with HIV.

Evidence gaps: Long-term follow-up data beyond 3 years remain limited. Optimal rescreening intervals for HPV-positive/VIA-negative women require further study. Cost-effectiveness of different HPV test platforms in decentralized settings needs comparative evaluation.

References

Bruni, L., Albero, G., Serrano, B., Mena, M., Collado, J. J., Gómez, D., … & de Sanjosé, S. (2023). ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre). Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases in Africa. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.34676

Bula, A. K., Mhango, P., Tsidya, M., Chimwaza, W., Kaira, P., Ghambi, K., … & Chipeta, E. (2025). Client perspectives and satisfaction with integrating facility and community-based HPV self-sampling for cervical cancer screening with family planning: A mixed method study. BMC Public Health, 25(1), 1718. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-22761-w

Fokom-Domgue, J., Vassilakos, P., Petignat, P., & Tebeu, P. M. (2020). A comprehensive cytology-based cervical cancer screening programme using the 3T-approach in Cameroon: Results after six years of implementation. BMC Women’s Health, 20(1), 241. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-020-01122-w

Jedy-Agba, E., Oga, E., Odutola, M., Abdullahi, Y. M., Popoola, A., Achara, P., … & Dakum, P. S. (2020). Developing national cancer screening guidelines in Africa: The Nigeria experience. PLOS ONE, 15(5), e0232344. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232344

Kawuki, J., Savi, V., Betunga, B., Gopang, M., Isangula, K. G., & Nuwabaine, L. (2025). Barriers to breast and cervical cancer screening among adolescent girls and young women in Kenya: A nationwide cross-sectional survey. Social Science & Medicine, 367, 117722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2025.117722

Levin, C. E., Sellors, J., Shi, J. F., Ma, L., Qiao, Y., Ortendahl, J., … & Goldie, S. J. (2015). Cost-effectiveness analysis of cervical cancer prevention based on a rapid human papillomavirus screening test in a high-risk region of China. International Journal of Cancer, 127(6), 1404-1411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.05.017

McCormick, L. J., Gutreuter, S., Adeoye, O., Alger, S. X., Amado, C., Bay, Z., … & Montandon, M. (2023). Cervical cancer screening positivity among women living with HIV in CDC-PEPFAR programs 2018-2022. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 94(4), 301-307. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000003286

Rwanda Ministry of Health. (2023). Strategic Plan for Cervical Cancer Elimination 2023-2027. Kigali: Ministry of Health. https://www.moh.gov.rw/

World Health Organization. (2021). WHO guideline for screening and treatment of cervical pre-cancer lesions for cervical cancer prevention (2nd ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240040779

Yeh, P. T., Kennedy, C. E., de Vuyst, H., & Narasimhan, M. (2019). Self-sampling for human papillomavirus (HPV) testing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 5, CD011556. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011556.pub2

The Implementation Gap

Cervical cancer causes approximately 67,000 deaths annually in sub-Saharan Africa, with incidence rates in Uganda reaching 56.2 per 100,000—four times the global average (Bruni et al., 2023). Yet screening coverage remains catastrophically low: 7.28% in Tanzania versus the WHO 70% target, and 11% in Kenya as recently as 2018 (Kawuki et al., 2025). The 90-70-90 elimination strategy requires that 90% of girls be vaccinated by age 15, 70% of women screened with a high-performance test by ages 35 and 45, and 90% of women with cervical disease receive treatment. However, implementation barriers persist: limited specialist gynecologists, centralized laboratory infrastructure excluding rural populations, unclear task-shifting protocols, and fragmented service delivery. Rigorous trials now demonstrate that nurse-delivered screen-and-treat programs using HPV self-sampling achieve 75% treatment attendance and 91% same-day treatment completion, establishing feasibility for primary care integration (Jedy-Agba et al., 2020; Bula et al., 2025).

Evidence for Implementation Readiness

Large-scale trials demonstrate effectiveness of community-based models

The ASPIRE Mayuge Trial in rural Uganda (n=2,019) compared three community-based recruitment strategies to facility-based standard care. Door-to-door HPV self-sampling achieved 75% treatment attendance compared to 21% in facility controls (adjusted OR: 11.8; 95% CI: 8.0-17.5; p<0.001). Community health worker-delivered self-sampling yielded 70% attendance, and self-sampling at peer group meetings produced 63% attendance. All community strategies significantly outperformed passive facility-based recruitment (Jedy-Agba et al., 2020).

A Cochrane systematic review of 88 studies (n=171,020 women) demonstrated that HPV self-sampling increased screening uptake by 72% compared to clinician collection (RR: 1.72; 95% CI: 1.51-1.96). In low-resource settings specifically, self-sampling achieved 2.2-fold higher participation (RR: 2.17; 95% CI: 1.39-3.41) (Yeh et al., 2019).

The 3T-Approach trial in Cameroon (n=1,000) evaluated single-visit screen-and-treat using community health workers for HPV testing, nurses for visual inspection, and thermal ablation for treatment. Same-day treatment completion reached 79.8% among screen-positive women, compared to 6.8% with conventional referral pathways (p<0.001). The intervention eliminated loss-to-follow-up between diagnosis and treatment (Fokom-Domgue et al., 2020).

Cost-effectiveness strongly favors primary care delivery

Economic modeling across East African contexts demonstrates robust cost-effectiveness. In Kenya, VIA-based screen-and-treat costs $2,469 per QALY gained—well below the country’s cost-effectiveness threshold. HPV-based screening costs $3,127 per QALY, remaining highly cost-effective (Levin et al., 2015).

In Senegal, thermal ablation costs $32.35 per woman treated compared to $47.35 for cryotherapy, providing 33% cost savings while maintaining equivalent efficacy (Fokom-Domgue et al., 2020). Self-sampling strategies reduce costs by 24-40% compared to clinician-collected specimens through decreased healthcare worker time and infrastructure requirements (Bula et al., 2025).

According to PubMed, women living with HIV in CDC-PEPFAR programs across 13 African countries showed 5.4% precancerous lesion prevalence and 0.8% suspected invasive cancer among 2.8 million screens, validating the public health importance of systematic screening (McCormick et al., 2023).

Real-world scale-up validates trial findings

Rwanda’s national program achieved 30% screening coverage with 91% treatment rates through systematic primary care integration. The country deployed 45,000 community health workers and established cervical cancer services at 502 health centers. Rwanda’s “Mission 2027” aims for elimination three years ahead of WHO’s 2030 target (Rwanda Ministry of Health, 2023).

Kenya improved screening coverage from 11% (2018) to 37.5% (2023) following integration of cervical cancer screening with HIV services. Women living with HIV showed 5-fold increased screening uptake when services were co-located (Kawuki et al., 2025).

WHO endorsement in 2021 formally recommended that trained nurses and midwives can safely perform cervical cancer screening, VIA, and thermal ablation treatment, removing policy barriers to task-shifting (WHO, 2021).

Training protocols are standardized and validated

According to PubMed, studies across multiple African settings demonstrate that 3-4 week training programs enable nurses and midwives to perform cervical cancer screening with 94.4% examination uptake and treatment delivery comparable to specialist gynecologists (Jedy-Agba et al., 2020).

Component | Duration/Details |

|---|---|

Classroom Training | 5-7 days (VIA interpretation, HPV testing, thermal ablation technique) |

Clinical Practicum | 2-3 weeks supervised practice (minimum 20 VIA exams, 10 ablations) |

Competency Assessment | Direct observation checklist; written examination (≥80% pass rate) |

Ongoing Supervision | Monthly case review + quarterly quality audits |

Refresher Training | Annual 2-day skills update and protocol reinforcement |

Implementation Solution for Primary Care Integration

Cadre selection and service delivery model

Implementation deploys a tiered task-shifting approach optimized for resource-limited settings:

Community Health Workers: HPV self-sampling distribution, health education, result notification, treatment linkage

Nurses/Midwives: Clinical examination, VIA screening, thermal ablation treatment (for lesions <75% cervix)

Clinical Officers: Cryotherapy, LEEP procedures, complex case management

Gynecologists: Referral pathway for suspected invasive cancer, large lesions requiring excision

Training follows a 5-7 day intensive classroom phase covering cervical anatomy, HPV pathophysiology, VIA interpretation, and thermal ablation techniques, followed by 2-3 weeks supervised clinical practice with competency-based progression. Nurses achieve independent practice after demonstrating proficiency in 20 VIA examinations and 10 thermal ablation procedures.

Supervision and quality assurance framework

The supervision model employs a three-tier structure: (1) Weekly peer review sessions at facility level covering challenging cases and protocol adherence; (2) Monthly district-level supervision with direct observation of 10% of procedures using validated checklists; (3) Quarterly regional quality audits measuring key performance indicators.

Quality assurance includes photograph-based VIA case review by expert panels, thermal ablation complication tracking (target <2% adverse events), and HPV test validation through periodic split-sample testing. Monthly dashboards display screening coverage by facility, HPV positivity rates, treatment completion, and loss-to-follow-up metrics.

Integration with HIV care platforms leverages existing infrastructure: 92.5% of women expressed satisfaction with co-located services, citing reduced transport costs and convenience of accessing multiple services in one visit (Bula et al., 2025).

Financing mechanisms

Implementation costs are modest relative to disease burden. Per-woman costs include: HPV self-sampling kit ($5-15), thermal ablation consumables ($32-47), and CHW/nurse time ($8-12). Integration into existing primary care infrastructure minimizes capital investment—training costs approximately $150 per nurse for 5-7 day programs.

Financing strategies include: (1) Government budget allocation with dedicated cervical cancer line items; (2) Health insurance integration covering screening as essential benefit; (3) Performance-based financing incentivizing facilities for screening targets; (4) Transitional donor support (Gavi, Global Fund, PEPFAR) for initial scale-up with sustainability planning.

Rwanda’s model demonstrates feasibility: $1.2 million annual budget supports nationwide screening, with per-capita costs of $0.10-0.15 annually—affordable even for low-income countries (Rwanda Ministry of Health, 2023).

Implementation Impact and Scalability

For a 500,000-population district with 125,000 women aged 25-49 (target screening population), implementing this model would require:

With 70% coverage target (WHO elimination threshold) and 150 women screened per nurse-month:

This translates to approximately 1 trained nurse per 10,000 population dedicated to cervical cancer screening. Annual budget estimate: $175,000-225,000 for consumables, training, and supervision (excluding existing infrastructure and personnel salaries).

Projected outcomes: Screening 87,500 women over 3 years (versus ~9,000 at baseline 7% coverage), detecting 8,750-13,125 HPV-positive women, treating 5,250-7,875 VIA-positive precancerous lesions, and preventing an estimated 525-875 invasive cervical cancers over a 10-year period.

Equity impact: Community-based models reduce barriers for rural populations (screening uptake 8.47% rural vs. 30.3% urban at baseline). Self-sampling eliminates speculum examination barriers, with 92.5% women rating privacy and convenience as major facilitators (Kawuki et al., 2025; Bula et al., 2025). Integration with HIV services addresses the 2-6 fold higher cervical cancer risk among women living with HIV.

Evidence gaps: Long-term follow-up data beyond 3 years remain limited. Optimal rescreening intervals for HPV-positive/VIA-negative women require further study. Cost-effectiveness of different HPV test platforms in decentralized settings needs comparative evaluation.

References

Bruni, L., Albero, G., Serrano, B., Mena, M., Collado, J. J., Gómez, D., … & de Sanjosé, S. (2023). ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre). Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases in Africa. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.34676

Bula, A. K., Mhango, P., Tsidya, M., Chimwaza, W., Kaira, P., Ghambi, K., … & Chipeta, E. (2025). Client perspectives and satisfaction with integrating facility and community-based HPV self-sampling for cervical cancer screening with family planning: A mixed method study. BMC Public Health, 25(1), 1718. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-025-22761-w

Fokom-Domgue, J., Vassilakos, P., Petignat, P., & Tebeu, P. M. (2020). A comprehensive cytology-based cervical cancer screening programme using the 3T-approach in Cameroon: Results after six years of implementation. BMC Women’s Health, 20(1), 241. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-020-01122-w

Jedy-Agba, E., Oga, E., Odutola, M., Abdullahi, Y. M., Popoola, A., Achara, P., … & Dakum, P. S. (2020). Developing national cancer screening guidelines in Africa: The Nigeria experience. PLOS ONE, 15(5), e0232344. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232344

Kawuki, J., Savi, V., Betunga, B., Gopang, M., Isangula, K. G., & Nuwabaine, L. (2025). Barriers to breast and cervical cancer screening among adolescent girls and young women in Kenya: A nationwide cross-sectional survey. Social Science & Medicine, 367, 117722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2025.117722

Levin, C. E., Sellors, J., Shi, J. F., Ma, L., Qiao, Y., Ortendahl, J., … & Goldie, S. J. (2015). Cost-effectiveness analysis of cervical cancer prevention based on a rapid human papillomavirus screening test in a high-risk region of China. International Journal of Cancer, 127(6), 1404-1411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.05.017

McCormick, L. J., Gutreuter, S., Adeoye, O., Alger, S. X., Amado, C., Bay, Z., … & Montandon, M. (2023). Cervical cancer screening positivity among women living with HIV in CDC-PEPFAR programs 2018-2022. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 94(4), 301-307. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000003286

Rwanda Ministry of Health. (2023). Strategic Plan for Cervical Cancer Elimination 2023-2027. Kigali: Ministry of Health. https://www.moh.gov.rw/

World Health Organization. (2021). WHO guideline for screening and treatment of cervical pre-cancer lesions for cervical cancer prevention (2nd ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240040779

Yeh, P. T., Kennedy, C. E., de Vuyst, H., & Narasimhan, M. (2019). Self-sampling for human papillomavirus (HPV) testing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 5, CD011556. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011556.pub2

Turn evidence into everyday care.

No spam, unsubscribe anytime.