Task-Shifting Mental Health Care in Low-Resource Settings

Verified by Sahaj Satani from ImplementMD

The Implementation Gap

Mental disorders affect 1 in 4 individuals globally, with depression and anxiety contributing 792 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) annually. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), the treatment gap reaches catastrophic proportions—75-90% of individuals requiring mental health care never receive it (Connery et al., 2020). Zimbabwe exemplifies this crisis: only 18 psychiatrists and 6 clinical psychologists serve a population of 17 million, with mental health receiving just 0.42% of the healthcare budget (Chibanda et al., 2016). However, rigorous trials now demonstrate that trained non-specialist providers—community health workers, lay counselors, and peer supporters—can deliver evidence-based psychological interventions with efficacy equivalent to or exceeding specialist care. The remaining barriers are implementation-focused: lack of standardized training programs, unclear primary care integration pathways, limited supervision infrastructure, and insufficient quality assurance systems.

Evidence for Implementation Readiness

Large-scale RCTs demonstrate robust effectiveness

The Friendship Bench trial in Zimbabwe (n=573) randomized 24 primary care clinics to intervention or control conditions. Lay health workers ("grandmothers") with no prior medical training delivered 6-session problem-solving therapy after 8 days of structured training plus a 30-day internship. At 6-month follow-up, only 13.7% of intervention participants remained symptomatic for depression compared to 49.9% in controls (adjusted risk ratio: 0.28; 95% CI: 0.22-0.36; p<.001). Suicidal ideation decreased from 12% to 2% in the intervention arm (Chibanda et al., 2016).

The MANAS trial in Goa, India (n=2,796) evaluated collaborative stepped care delivered by lay health counselors in 24 primary care facilities. Among public facility patients with ICD-10 confirmed common mental disorders, recovery rates reached 65.9% in the intervention arm versus 42.5% in controls (RR: 1.55; 95% CI: 1.02-2.35). At 12-month follow-up, suicide attempts/plans decreased by 36% (RR: 0.64; 95% CI: 0.42-0.98) (Patel et al., 2010; Patel et al., 2011).

The Thinking Healthy Programme (THP) cluster RCT in Pakistan (n=903) trained Lady Health Workers to deliver CBT-based perinatal depression treatment across 40 village clusters. Major depression prevalence dropped from baseline to 23% in the intervention arm versus 53% in controls at 6 months (adjusted OR: 0.22; 95% CI: 0.14-0.36; p<.0001), with effects sustained at 12 months (OR: 0.23) (Rahman et al., 2008).

The Healthy Activity Program (HAP) trial in India (n=495 with moderately severe to severe depression, PHQ-9 >14) demonstrated that lay counselor-delivered behavioral activation significantly improved remission rates (RR: 1.61), reduced days out of work by 2.29 days (95% CI: -3.84 to -0.73; p=.004), and decreased intimate partner violence among women (OR: 0.53; 95% CI: 0.29-0.96) (Patel et al., 2017).

Cost-effectiveness favors task-shifted models

Economic evaluations embedded within these trials demonstrate exceptional value. The MANAS intervention achieved cost savings of US$52 per patient while improving outcomes—the intervention cost only US$2 per participant in human resource costs (Buttorff et al., 2012). The THP costs under US$10 per woman treated, while the technology-assisted peer-delivered version (THP-TAP) reduced delivery costs to US$24 per patient compared to US$44 for standard implementation (Gibbs et al., 2025). The HAP trial reported an incremental cost of US$9,333 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained, with 87% probability of cost-effectiveness (Patel et al., 2017). Global modeling for adolescent mental health interventions estimates a cost of US$102.90 per DALY averted with a 23.6:1 return on investment (Stelmach et al., 2022).

Real-world scale-up validates trial findings

Zimbabwe's Friendship Bench has expanded to all 10 provinces, training 3,000+ community health workers who have served over 700,000 clients since national rollout in 2022. India's District Mental Health Programme now covers 767 districts (90%), with Tamil Nadu alone serving 805,896 patients from April 2022-August 2023. The WHO mhGAP Intervention Guide has been implemented in 90+ countries, with standardized 5-day training achieving >80% diagnostic concordance with structured clinical interviews in Kenya (Mutiso et al., 2018).

Training protocols are standardized and replicable

Component | Duration/Details |

|---|---|

Classroom Training | 5-10 days (mhGAP-IG: 5 days; Friendship Bench: 8 days; THP: 4 days) |

Supervised Practice | 30-day internship (Friendship Bench) to 6-month field training (THP cascade) |

Competency Assessment | ENACT 18-item scale; therapy-specific checklists |

Ongoing Supervision | Weekly group (2-3 hours) + monthly individual (30 min) |

Fidelity Monitoring | Audio recording review; session checklists; live observation |

Implementation Solution for Primary Care Integration

Cadre selection and training curriculum

Implementation should deploy a mixed-cadre approach tailored to local context. Recommended providers include:

Community Health Workers (CHWs): Screening, case identification, basic psychoeducation

Lay Counselors: Structured problem-solving therapy, behavioral activation (4-8 sessions)

Primary Care Nurses: mhGAP-IG protocol implementation, medication monitoring

Peer Supporters: Ongoing support groups, relapse prevention

Training follows a 3-4 week intensive phase combining classroom instruction (didactics, role-play, case studies) with supervised practice, followed by 4-8 weeks of graduated clinical experience with fidelity monitoring.

Service delivery model and clinical workflow

Supervision and quality assurance

The supervision framework mirrors the AFFIRM-SA model: weekly group supervision (2-3 hours) with a trained mental health counselor covering case discussions, skills practice, and debriefing; monthly individual supervision (30 minutes) for complex cases; and specialist oversight twice monthly via telesupervision. Remote supervision using phone/video enables rural coverage. Quality assurance includes the ENACT competency tool (18-item scale validated across multiple LMIC contexts), random audio recording review of sessions, and real-time outcome tracking via PHQ-9/GAD-7 at each session.

Financing mechanisms

Integration into existing primary care budgets minimizes incremental costs. The estimated US$0.18-0.55 per capita annually required for scale-up can be financed through government budget allocation, performance-based financing tied to mental health indicators, and phased donor-to-government transition models (Chisholm et al., 2007). The demonstrated cost-savings (MANAS: US$52 saved per patient) support sustainability arguments.

Implementation Impact and Scalability

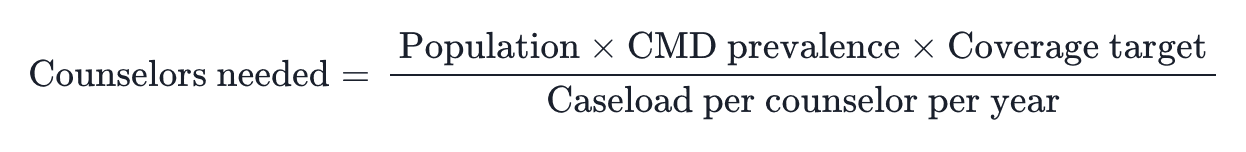

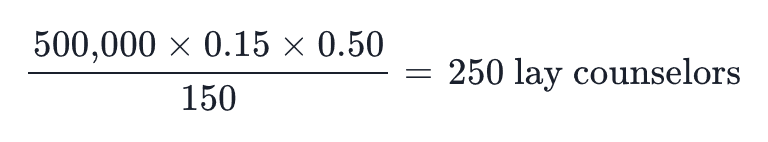

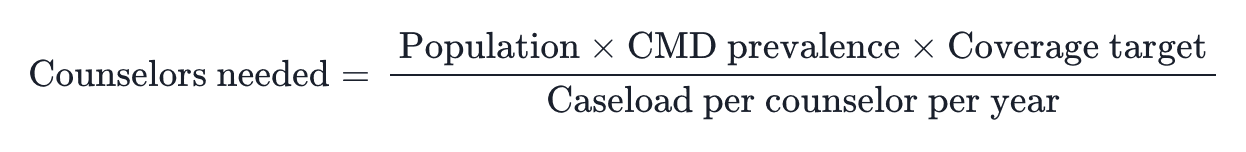

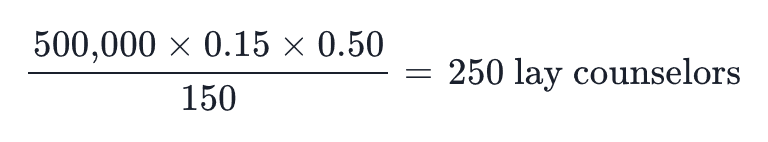

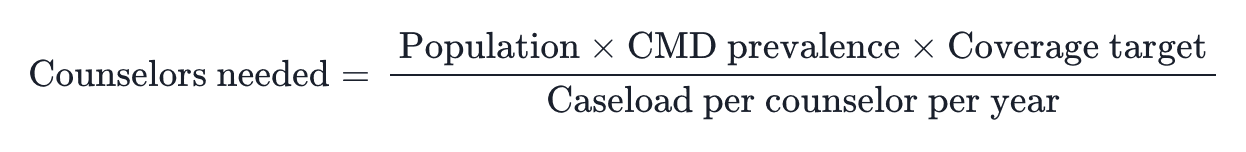

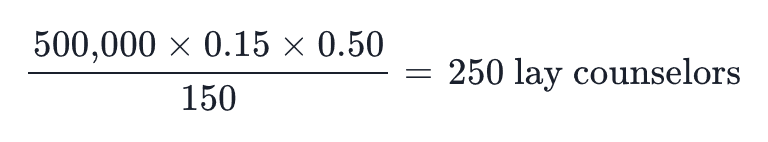

For a 500,000-population district with baseline treatment gap of 90%, implementing this model would require:

With 15% CMD prevalence, 50% coverage target, and 150 patients/counselor/year:

This translates to approximately 1 counselor per 2,000 population. Annual budget estimate: US$925,000-1,375,000 (US$0.18-0.55 × 500,000 + training costs), with potential cost-savings offsetting investment.

Projected outcomes: Treating 37,500 patients annually (versus <3,750 at baseline), achieving 60-65% remission rates, reducing treatment gap from 90% to approximately 50% within 3 years. Equity impact: prioritized reach to women (perinatal), adolescents, rural populations, and refugees through community-embedded, culturally-adapted delivery.

References

Buttorff, C., Hock, R. S., Weiss, H. A., Naik, S., Araya, R., Kirkwood, B. R., ... & Patel, V. (2012). Economic evaluation of a task-shifting intervention for common mental disorders in India. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 90(11), 813-821. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.12.104133

Chibanda, D., Weiss, H. A., Verhey, R., Simms, V., Munjoma, R., Rusakaniko, S., ... & Araya, R. (2016). Effect of a primary care–based psychological intervention on symptoms of common mental disorders in Zimbabwe: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 316(24), 2618-2626. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.19102

Chisholm, D., Lund, C., & Saxena, S. (2007). Cost of scaling up mental healthcare in low- and middle-income countries. British Journal of Psychiatry, 191(6), 528-535. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.107.038463

Kohrt, B. A., Jordans, M. J., Ber, W. A., Koirala, S., Upadhaya, N., & Luitel, N. P. (2015). Designing mental health interventions informed by child development and human biology theory: A social ecology intervention for child soldiers in Nepal. American Journal of Human Biology, 27(1), 27-40. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.22651

Mutiso, V. N., Gitonga, I., Musau, A., Tele, A., Sabina, W., Ndetei, D. M., ... & Pike, K. M. (2018). Patterns of concordances in mhGAP-IG screening and DSM-IV/ICD10 diagnoses by trained community service providers in Kenya. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53(11), 1277-1287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1567-1

Patel, V., Weiss, H. A., Chowdhary, N., Naik, S., Pednekar, S., Chatterjee, S., ... & Kirkwood, B. R. (2010). Effectiveness of an intervention led by lay health counsellors for depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care in Goa, India (MANAS): A cluster randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 376(9758), 2086-2095. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61508-5

Patel, V., Weobong, B., Weiss, H. A., Anand, A., Bhat, B., Katti, B., ... & Fairburn, C. G. (2017). The Healthy Activity Program (HAP), a lay counsellor-delivered brief psychological treatment for severe depression, in primary care in India: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 389(10065), 176-185. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31589-6

Rahman, A., Malik, A., Sikander, S., Roberts, C., & Creed, F. (2008). Cognitive behaviour therapy-based intervention by community health workers for mothers with depression and their infants in rural Pakistan: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 372(9642), 902-909. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61400-2

Stelmach, R., Kocher, E. L., Kataria, I., Jackson-Morris, A. M., Saxena, S., & Nugent, R. (2022). The global return on investment from preventing and treating adolescent mental disorders and suicide: A modelling study. BMJ Global Health, 7(6), e007759. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007759

The Implementation Gap

Mental disorders affect 1 in 4 individuals globally, with depression and anxiety contributing 792 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) annually. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), the treatment gap reaches catastrophic proportions—75-90% of individuals requiring mental health care never receive it (Connery et al., 2020). Zimbabwe exemplifies this crisis: only 18 psychiatrists and 6 clinical psychologists serve a population of 17 million, with mental health receiving just 0.42% of the healthcare budget (Chibanda et al., 2016). However, rigorous trials now demonstrate that trained non-specialist providers—community health workers, lay counselors, and peer supporters—can deliver evidence-based psychological interventions with efficacy equivalent to or exceeding specialist care. The remaining barriers are implementation-focused: lack of standardized training programs, unclear primary care integration pathways, limited supervision infrastructure, and insufficient quality assurance systems.

Evidence for Implementation Readiness

Large-scale RCTs demonstrate robust effectiveness

The Friendship Bench trial in Zimbabwe (n=573) randomized 24 primary care clinics to intervention or control conditions. Lay health workers ("grandmothers") with no prior medical training delivered 6-session problem-solving therapy after 8 days of structured training plus a 30-day internship. At 6-month follow-up, only 13.7% of intervention participants remained symptomatic for depression compared to 49.9% in controls (adjusted risk ratio: 0.28; 95% CI: 0.22-0.36; p<.001). Suicidal ideation decreased from 12% to 2% in the intervention arm (Chibanda et al., 2016).

The MANAS trial in Goa, India (n=2,796) evaluated collaborative stepped care delivered by lay health counselors in 24 primary care facilities. Among public facility patients with ICD-10 confirmed common mental disorders, recovery rates reached 65.9% in the intervention arm versus 42.5% in controls (RR: 1.55; 95% CI: 1.02-2.35). At 12-month follow-up, suicide attempts/plans decreased by 36% (RR: 0.64; 95% CI: 0.42-0.98) (Patel et al., 2010; Patel et al., 2011).

The Thinking Healthy Programme (THP) cluster RCT in Pakistan (n=903) trained Lady Health Workers to deliver CBT-based perinatal depression treatment across 40 village clusters. Major depression prevalence dropped from baseline to 23% in the intervention arm versus 53% in controls at 6 months (adjusted OR: 0.22; 95% CI: 0.14-0.36; p<.0001), with effects sustained at 12 months (OR: 0.23) (Rahman et al., 2008).

The Healthy Activity Program (HAP) trial in India (n=495 with moderately severe to severe depression, PHQ-9 >14) demonstrated that lay counselor-delivered behavioral activation significantly improved remission rates (RR: 1.61), reduced days out of work by 2.29 days (95% CI: -3.84 to -0.73; p=.004), and decreased intimate partner violence among women (OR: 0.53; 95% CI: 0.29-0.96) (Patel et al., 2017).

Cost-effectiveness favors task-shifted models

Economic evaluations embedded within these trials demonstrate exceptional value. The MANAS intervention achieved cost savings of US$52 per patient while improving outcomes—the intervention cost only US$2 per participant in human resource costs (Buttorff et al., 2012). The THP costs under US$10 per woman treated, while the technology-assisted peer-delivered version (THP-TAP) reduced delivery costs to US$24 per patient compared to US$44 for standard implementation (Gibbs et al., 2025). The HAP trial reported an incremental cost of US$9,333 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained, with 87% probability of cost-effectiveness (Patel et al., 2017). Global modeling for adolescent mental health interventions estimates a cost of US$102.90 per DALY averted with a 23.6:1 return on investment (Stelmach et al., 2022).

Real-world scale-up validates trial findings

Zimbabwe's Friendship Bench has expanded to all 10 provinces, training 3,000+ community health workers who have served over 700,000 clients since national rollout in 2022. India's District Mental Health Programme now covers 767 districts (90%), with Tamil Nadu alone serving 805,896 patients from April 2022-August 2023. The WHO mhGAP Intervention Guide has been implemented in 90+ countries, with standardized 5-day training achieving >80% diagnostic concordance with structured clinical interviews in Kenya (Mutiso et al., 2018).

Training protocols are standardized and replicable

Component | Duration/Details |

|---|---|

Classroom Training | 5-10 days (mhGAP-IG: 5 days; Friendship Bench: 8 days; THP: 4 days) |

Supervised Practice | 30-day internship (Friendship Bench) to 6-month field training (THP cascade) |

Competency Assessment | ENACT 18-item scale; therapy-specific checklists |

Ongoing Supervision | Weekly group (2-3 hours) + monthly individual (30 min) |

Fidelity Monitoring | Audio recording review; session checklists; live observation |

Implementation Solution for Primary Care Integration

Cadre selection and training curriculum

Implementation should deploy a mixed-cadre approach tailored to local context. Recommended providers include:

Community Health Workers (CHWs): Screening, case identification, basic psychoeducation

Lay Counselors: Structured problem-solving therapy, behavioral activation (4-8 sessions)

Primary Care Nurses: mhGAP-IG protocol implementation, medication monitoring

Peer Supporters: Ongoing support groups, relapse prevention

Training follows a 3-4 week intensive phase combining classroom instruction (didactics, role-play, case studies) with supervised practice, followed by 4-8 weeks of graduated clinical experience with fidelity monitoring.

Service delivery model and clinical workflow

Supervision and quality assurance

The supervision framework mirrors the AFFIRM-SA model: weekly group supervision (2-3 hours) with a trained mental health counselor covering case discussions, skills practice, and debriefing; monthly individual supervision (30 minutes) for complex cases; and specialist oversight twice monthly via telesupervision. Remote supervision using phone/video enables rural coverage. Quality assurance includes the ENACT competency tool (18-item scale validated across multiple LMIC contexts), random audio recording review of sessions, and real-time outcome tracking via PHQ-9/GAD-7 at each session.

Financing mechanisms

Integration into existing primary care budgets minimizes incremental costs. The estimated US$0.18-0.55 per capita annually required for scale-up can be financed through government budget allocation, performance-based financing tied to mental health indicators, and phased donor-to-government transition models (Chisholm et al., 2007). The demonstrated cost-savings (MANAS: US$52 saved per patient) support sustainability arguments.

Implementation Impact and Scalability

For a 500,000-population district with baseline treatment gap of 90%, implementing this model would require:

With 15% CMD prevalence, 50% coverage target, and 150 patients/counselor/year:

This translates to approximately 1 counselor per 2,000 population. Annual budget estimate: US$925,000-1,375,000 (US$0.18-0.55 × 500,000 + training costs), with potential cost-savings offsetting investment.

Projected outcomes: Treating 37,500 patients annually (versus <3,750 at baseline), achieving 60-65% remission rates, reducing treatment gap from 90% to approximately 50% within 3 years. Equity impact: prioritized reach to women (perinatal), adolescents, rural populations, and refugees through community-embedded, culturally-adapted delivery.

References

Buttorff, C., Hock, R. S., Weiss, H. A., Naik, S., Araya, R., Kirkwood, B. R., ... & Patel, V. (2012). Economic evaluation of a task-shifting intervention for common mental disorders in India. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 90(11), 813-821. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.12.104133

Chibanda, D., Weiss, H. A., Verhey, R., Simms, V., Munjoma, R., Rusakaniko, S., ... & Araya, R. (2016). Effect of a primary care–based psychological intervention on symptoms of common mental disorders in Zimbabwe: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 316(24), 2618-2626. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.19102

Chisholm, D., Lund, C., & Saxena, S. (2007). Cost of scaling up mental healthcare in low- and middle-income countries. British Journal of Psychiatry, 191(6), 528-535. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.107.038463

Kohrt, B. A., Jordans, M. J., Ber, W. A., Koirala, S., Upadhaya, N., & Luitel, N. P. (2015). Designing mental health interventions informed by child development and human biology theory: A social ecology intervention for child soldiers in Nepal. American Journal of Human Biology, 27(1), 27-40. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.22651

Mutiso, V. N., Gitonga, I., Musau, A., Tele, A., Sabina, W., Ndetei, D. M., ... & Pike, K. M. (2018). Patterns of concordances in mhGAP-IG screening and DSM-IV/ICD10 diagnoses by trained community service providers in Kenya. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53(11), 1277-1287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1567-1

Patel, V., Weiss, H. A., Chowdhary, N., Naik, S., Pednekar, S., Chatterjee, S., ... & Kirkwood, B. R. (2010). Effectiveness of an intervention led by lay health counsellors for depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care in Goa, India (MANAS): A cluster randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 376(9758), 2086-2095. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61508-5

Patel, V., Weobong, B., Weiss, H. A., Anand, A., Bhat, B., Katti, B., ... & Fairburn, C. G. (2017). The Healthy Activity Program (HAP), a lay counsellor-delivered brief psychological treatment for severe depression, in primary care in India: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 389(10065), 176-185. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31589-6

Rahman, A., Malik, A., Sikander, S., Roberts, C., & Creed, F. (2008). Cognitive behaviour therapy-based intervention by community health workers for mothers with depression and their infants in rural Pakistan: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 372(9642), 902-909. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61400-2

Stelmach, R., Kocher, E. L., Kataria, I., Jackson-Morris, A. M., Saxena, S., & Nugent, R. (2022). The global return on investment from preventing and treating adolescent mental disorders and suicide: A modelling study. BMJ Global Health, 7(6), e007759. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007759

The Implementation Gap

Mental disorders affect 1 in 4 individuals globally, with depression and anxiety contributing 792 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) annually. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), the treatment gap reaches catastrophic proportions—75-90% of individuals requiring mental health care never receive it (Connery et al., 2020). Zimbabwe exemplifies this crisis: only 18 psychiatrists and 6 clinical psychologists serve a population of 17 million, with mental health receiving just 0.42% of the healthcare budget (Chibanda et al., 2016). However, rigorous trials now demonstrate that trained non-specialist providers—community health workers, lay counselors, and peer supporters—can deliver evidence-based psychological interventions with efficacy equivalent to or exceeding specialist care. The remaining barriers are implementation-focused: lack of standardized training programs, unclear primary care integration pathways, limited supervision infrastructure, and insufficient quality assurance systems.

Evidence for Implementation Readiness

Large-scale RCTs demonstrate robust effectiveness

The Friendship Bench trial in Zimbabwe (n=573) randomized 24 primary care clinics to intervention or control conditions. Lay health workers ("grandmothers") with no prior medical training delivered 6-session problem-solving therapy after 8 days of structured training plus a 30-day internship. At 6-month follow-up, only 13.7% of intervention participants remained symptomatic for depression compared to 49.9% in controls (adjusted risk ratio: 0.28; 95% CI: 0.22-0.36; p<.001). Suicidal ideation decreased from 12% to 2% in the intervention arm (Chibanda et al., 2016).

The MANAS trial in Goa, India (n=2,796) evaluated collaborative stepped care delivered by lay health counselors in 24 primary care facilities. Among public facility patients with ICD-10 confirmed common mental disorders, recovery rates reached 65.9% in the intervention arm versus 42.5% in controls (RR: 1.55; 95% CI: 1.02-2.35). At 12-month follow-up, suicide attempts/plans decreased by 36% (RR: 0.64; 95% CI: 0.42-0.98) (Patel et al., 2010; Patel et al., 2011).

The Thinking Healthy Programme (THP) cluster RCT in Pakistan (n=903) trained Lady Health Workers to deliver CBT-based perinatal depression treatment across 40 village clusters. Major depression prevalence dropped from baseline to 23% in the intervention arm versus 53% in controls at 6 months (adjusted OR: 0.22; 95% CI: 0.14-0.36; p<.0001), with effects sustained at 12 months (OR: 0.23) (Rahman et al., 2008).

The Healthy Activity Program (HAP) trial in India (n=495 with moderately severe to severe depression, PHQ-9 >14) demonstrated that lay counselor-delivered behavioral activation significantly improved remission rates (RR: 1.61), reduced days out of work by 2.29 days (95% CI: -3.84 to -0.73; p=.004), and decreased intimate partner violence among women (OR: 0.53; 95% CI: 0.29-0.96) (Patel et al., 2017).

Cost-effectiveness favors task-shifted models

Economic evaluations embedded within these trials demonstrate exceptional value. The MANAS intervention achieved cost savings of US$52 per patient while improving outcomes—the intervention cost only US$2 per participant in human resource costs (Buttorff et al., 2012). The THP costs under US$10 per woman treated, while the technology-assisted peer-delivered version (THP-TAP) reduced delivery costs to US$24 per patient compared to US$44 for standard implementation (Gibbs et al., 2025). The HAP trial reported an incremental cost of US$9,333 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained, with 87% probability of cost-effectiveness (Patel et al., 2017). Global modeling for adolescent mental health interventions estimates a cost of US$102.90 per DALY averted with a 23.6:1 return on investment (Stelmach et al., 2022).

Real-world scale-up validates trial findings

Zimbabwe's Friendship Bench has expanded to all 10 provinces, training 3,000+ community health workers who have served over 700,000 clients since national rollout in 2022. India's District Mental Health Programme now covers 767 districts (90%), with Tamil Nadu alone serving 805,896 patients from April 2022-August 2023. The WHO mhGAP Intervention Guide has been implemented in 90+ countries, with standardized 5-day training achieving >80% diagnostic concordance with structured clinical interviews in Kenya (Mutiso et al., 2018).

Training protocols are standardized and replicable

Component | Duration/Details |

|---|---|

Classroom Training | 5-10 days (mhGAP-IG: 5 days; Friendship Bench: 8 days; THP: 4 days) |

Supervised Practice | 30-day internship (Friendship Bench) to 6-month field training (THP cascade) |

Competency Assessment | ENACT 18-item scale; therapy-specific checklists |

Ongoing Supervision | Weekly group (2-3 hours) + monthly individual (30 min) |

Fidelity Monitoring | Audio recording review; session checklists; live observation |

Implementation Solution for Primary Care Integration

Cadre selection and training curriculum

Implementation should deploy a mixed-cadre approach tailored to local context. Recommended providers include:

Community Health Workers (CHWs): Screening, case identification, basic psychoeducation

Lay Counselors: Structured problem-solving therapy, behavioral activation (4-8 sessions)

Primary Care Nurses: mhGAP-IG protocol implementation, medication monitoring

Peer Supporters: Ongoing support groups, relapse prevention

Training follows a 3-4 week intensive phase combining classroom instruction (didactics, role-play, case studies) with supervised practice, followed by 4-8 weeks of graduated clinical experience with fidelity monitoring.

Service delivery model and clinical workflow

Supervision and quality assurance

The supervision framework mirrors the AFFIRM-SA model: weekly group supervision (2-3 hours) with a trained mental health counselor covering case discussions, skills practice, and debriefing; monthly individual supervision (30 minutes) for complex cases; and specialist oversight twice monthly via telesupervision. Remote supervision using phone/video enables rural coverage. Quality assurance includes the ENACT competency tool (18-item scale validated across multiple LMIC contexts), random audio recording review of sessions, and real-time outcome tracking via PHQ-9/GAD-7 at each session.

Financing mechanisms

Integration into existing primary care budgets minimizes incremental costs. The estimated US$0.18-0.55 per capita annually required for scale-up can be financed through government budget allocation, performance-based financing tied to mental health indicators, and phased donor-to-government transition models (Chisholm et al., 2007). The demonstrated cost-savings (MANAS: US$52 saved per patient) support sustainability arguments.

Implementation Impact and Scalability

For a 500,000-population district with baseline treatment gap of 90%, implementing this model would require:

With 15% CMD prevalence, 50% coverage target, and 150 patients/counselor/year:

This translates to approximately 1 counselor per 2,000 population. Annual budget estimate: US$925,000-1,375,000 (US$0.18-0.55 × 500,000 + training costs), with potential cost-savings offsetting investment.

Projected outcomes: Treating 37,500 patients annually (versus <3,750 at baseline), achieving 60-65% remission rates, reducing treatment gap from 90% to approximately 50% within 3 years. Equity impact: prioritized reach to women (perinatal), adolescents, rural populations, and refugees through community-embedded, culturally-adapted delivery.

References

Buttorff, C., Hock, R. S., Weiss, H. A., Naik, S., Araya, R., Kirkwood, B. R., ... & Patel, V. (2012). Economic evaluation of a task-shifting intervention for common mental disorders in India. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 90(11), 813-821. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.12.104133

Chibanda, D., Weiss, H. A., Verhey, R., Simms, V., Munjoma, R., Rusakaniko, S., ... & Araya, R. (2016). Effect of a primary care–based psychological intervention on symptoms of common mental disorders in Zimbabwe: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 316(24), 2618-2626. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.19102

Chisholm, D., Lund, C., & Saxena, S. (2007). Cost of scaling up mental healthcare in low- and middle-income countries. British Journal of Psychiatry, 191(6), 528-535. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.107.038463

Kohrt, B. A., Jordans, M. J., Ber, W. A., Koirala, S., Upadhaya, N., & Luitel, N. P. (2015). Designing mental health interventions informed by child development and human biology theory: A social ecology intervention for child soldiers in Nepal. American Journal of Human Biology, 27(1), 27-40. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.22651

Mutiso, V. N., Gitonga, I., Musau, A., Tele, A., Sabina, W., Ndetei, D. M., ... & Pike, K. M. (2018). Patterns of concordances in mhGAP-IG screening and DSM-IV/ICD10 diagnoses by trained community service providers in Kenya. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 53(11), 1277-1287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1567-1

Patel, V., Weiss, H. A., Chowdhary, N., Naik, S., Pednekar, S., Chatterjee, S., ... & Kirkwood, B. R. (2010). Effectiveness of an intervention led by lay health counsellors for depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care in Goa, India (MANAS): A cluster randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 376(9758), 2086-2095. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61508-5

Patel, V., Weobong, B., Weiss, H. A., Anand, A., Bhat, B., Katti, B., ... & Fairburn, C. G. (2017). The Healthy Activity Program (HAP), a lay counsellor-delivered brief psychological treatment for severe depression, in primary care in India: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 389(10065), 176-185. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31589-6

Rahman, A., Malik, A., Sikander, S., Roberts, C., & Creed, F. (2008). Cognitive behaviour therapy-based intervention by community health workers for mothers with depression and their infants in rural Pakistan: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 372(9642), 902-909. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61400-2

Stelmach, R., Kocher, E. L., Kataria, I., Jackson-Morris, A. M., Saxena, S., & Nugent, R. (2022). The global return on investment from preventing and treating adolescent mental disorders and suicide: A modelling study. BMJ Global Health, 7(6), e007759. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007759

Turn evidence into everyday care.

No spam, unsubscribe anytime.